A LIGHT patter bounced off the titanium fish scales of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao as a tour bus pulled up beside “Puppy,” Jeff Koons's 43-foot-tall topiary terrier made of freshly potted pansies. A stream of tourists fanned out across the crisp limestone plaza, tripping over each other as they rushed to capture the moment on camera. After the frisson of excitement dimmed, they made their way down a gently sloping stairway and into the belly of the museum, paying 10.50 euros to see the work of an artist that most had never heard of.

It was a ritual that repeated itself several times an hour, like a well-run multiplex. And if Anselm Kiefer, the controversial post-war German artist, was eclipsed by the metallic blob that held a retrospective of his work, consider how Bilbao, a rusty port city on the northern coast of Spain, stacked up to the very museum that put it on the cultural map.

“We don't know anything about Bilbao besides the Guggenheim,” said Luigi Fattore, 28, a financial analyst from Paris, who was taking pictures of his girlfriend under the puppy. As if to underscore the point, they showed up at the museum's doorstep with their suitcase in tow. “We've arrived half an hour ago,” he said, “and went straight to the Guggenheim. Aside from the museum, we don't have any plans.”

Such is the staying power of Frank O. Gehry's architectural showstopper, 10 years after it crash-landed on the public psyche like a new Hollywood starlet. The iridescent structure wasn't just a new building; it was a cultural extravaganza.

No less an authority than Philip Johnson deemed it “the greatest building of our time.” The swooping form began showing up everywhere, from car ads to MTV rap videos, like architectural bling. And in certain artistic and architectural social circles, a pilgrimage to Bilbao became de rigueur, with the question “Have you been to Bilbao?” a kind of cocktail party game that marked someone either as a culture vulture or a clueless rube.

“No one had heard of Bilbao or knew where it was,” said Terence Riley, director of the Miami Art Museum and a former architecture and design curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. “Nobody knew how to spell it.”

The Guggenheim changed that overnight. Microsoft Word, Mr. Riley noted, added “Bilbao” to its spell checker. And as word of the Guggenheim spread, tourists of all stripes began converging onto the small industrial city — the Pittsburgh of Spain — just to check it off their list.

“I've been down there four times,” Mr. Riley added proudly. “That's probably more than most.”

Even for those who couldn't spell “Bilbao,” let alone pronounce it (bill-BAH-o), the city became synonymous with the ensuing worldwide rush by urbanists to erect trophy buildings, in the hopes of turning second-tier cities into tourist magnets. The so-called Bilbao Effect was studied in universities throughout the world as a textbook example of how to repackage cities with “wow-factor” architecture. And as cities from Denver to Dubai followed in Bilbao's footsteps, Mr. Gehry and his fellow starchitects were elevated to the role of urban messiahs.

But what has the Bilbao Effect meant for Bilbao?

I first visited Bilbao in 1999, a lone, wide-eyed tourist who had read about the “Miracle in Bilbao” on the cover of The New York Times Magazine, in which the paper's architecture critic, Herbert Muschamp, likened the “voluptuous” museum to “the reincarnation of Marilyn Monroe.” And on that cold and dark March afternoon, when the lush green folds of the region's coastal mountains were shrouded behind a gray veil, the Guggenheim indeed glinted like a blonde metallic bombshell.

After loading my 35-millimeter camera, I took pictures of the museum's sinuous curves, surreptitiously ran my fingers across the titanium shingles and marveled at the galleries' lack of right angles. Oh, there was art, too: Jenny Holzer's soaring L.E.D. columns, a collection of sketches from Albrecht Dürer to Robert Rauschenberg and — caged behind a chain-link fence in a parking lot — one of Richard Serra's “Torqued Ellipses” for a future exhibition.

But the thing that struck me most, more than the dazzling architecture or cool art, was the horrible smell. Here was this magnificent museum, the most celebrated piece of architecture in a generation, and yet the river beside it was as brown as sludge and as putrid as a sewer — a world-class museum swimming in third-world biohazard.

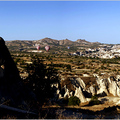

The Guggenheim, I later learned, was built on a former shipyard, and the Nervión River, which snakes through Bilbao to the Bay of Biscay, was the nexus of Spain's Industrial Revolution. Blessed with iron-rich mountains, railroads and an excellent port, Bilbao blossomed in the late 19th century with metalworks and shipbuilding. But a century of belching factories turned the mighty Nervión into a toxic cesspool, earning the city the unflattering nickname “El Botxo,” the Basque word for hole.

But the iron mines eventually gave out; shipbuilding moved to Asia. And when the Guggenheim opened its doors in October 1997, what remained was a Dickensian waterfront of rusting cargo rigs and hollow warehouses. Farther up the river, grease-coated factories croaked along its lifeless banks, like a cemetery for the Industrial Age.

The rest of the city hadn't fared much better. The boulevards radiating from the Guggenheim may have evoked grandeur with their neo-Baroque facades and monumentality, but they were caked in soot and sadly devoid of street life. Sure, there were other signs of design — the caterpillar-like entrances by Norman Foster for a new metro system, a sweeping footbridge by Santiago Calatrava — but they only made the city seem dingier, like a polished fork in a tray of dirty silverware.

But if Bilbao wasn't exactly ready for its tourist spotlight, the gray industrial air gave the city a raw authenticity and gritty undercurrent that was charmingly provincial. In the Casco Viejo quarter, on the other side of the river, the urine-soaked cobblestones and graffiti-covered walls (mostly in support of the Basque separatist group E.T.A.) may have needed a good scrub. But it felt like a real neighborhood, warts and all, that was proudly oblivious, bordering on rude, to tourists.

In the morning, stumpy grandmothers waited in line for fresh bread and Bayonne ham at antiquated shops. By noon, old men sat in dingy pintxos bars drinking txakoli, a semi-sparkling white wine. And when the weekend rolled around, the dark alleyways vibrated with roving bands of Basque youths stumbling between pubs and drinking kalimotxos, a local concoction made from cheap wine and cola. The futuristic Guggenheim seemed to be in another city, far removed from the grubby fish markets and well-tended flower boxes that gave old Bilbao its character.

That cultural schism, however, began to dissolve. In its first year, the Guggenheim was clocking about 100,000 visitors a month. And rather than drop off precipitously like a summer blockbuster, attendance rates have leveled off to “a cruising speed of around one million visitors a year,” said Juan Ignacio Vidarte, the Guggenheim's director, adding that the vast majority were from outside the Basque region, and more than half from other countries. By the end of 2006, some nine million visitors had paid homage to Gehry's miracle.

THE impact on this city of 354,000 was dramatic. Charmless business hotels and musty pensions were supplanted by trendy hotels like the Domine Bilbao and a Sheraton designed by the Mexican architect Ricardo Legorreta. The rusty shipyards near the Guggenheim were razed for a manicured greenbelt of playgrounds, bicycle paths and riverside cafes. A lime-green tram was strung along the river, linking the Guggenheim to Casco Viejo and beyond.

And all across the city, a who's who of architects added their marquee names to Bilbao's work-in-progress skyline: Álvaro Siza (university building), Cesar Pelli (40-story office tower), Santiago Calatrava (airport terminal), Zaha Hadid (master plan), Philippe Starck (wine warehouse conversion), Robert A. M. Stern (shopping mall) and Rafael Moneo (library), to name just a few. It's as if Bilbao went on a shopping spree, commissioning a trophy case of starchitects and Pritzker Architecture Prize winners.

A tangle of construction cranes today rises over the city's terra-cotta rooftops, but the changes are already apparent at the street level. Bilbao, a muscular town of steelworkers and engineers, is slowly becoming a more effete city of hotel clerks and art collectors.

The city's main artery, Gran Vía de Don Diego López de Haro, is no longer a soot-stained canyon of bank offices. In the tradition of the Champs-Élysées, the sidewalks were widened, curbside parking removed and stone buildings scrubbed. On a warm Friday last May, shoppers streamed out of countless Zara boutiques. Men in natty business suits sat on benches, smoking cigarettes and reading El País. In front of the opulent Hotel Carlton, a handsome couple was being married.

The beautification was echoed throughout the city. Traffic circles like Plazas Campuzano and Indauxtu had been transformed into piazza-like parks, with sculptural lampposts, ergonomic benches and ultramodern landscaping. In place of polluting cars, laughing children now use them as impromptu soccer fields.

Casco Viejo was almost unrecognizable. The graffiti had been erased. The stone facades sandblasted. And old butchers shared the sidewalk with H & M and Billabong.

At lunchtime, crowds converged on upscale pintxos bars like Sasibil, grazing on octopus and Iberian ham sandwiches, which were exhibited like jewelry under polished glass cases and halogen lights. After sundown, well-dressed couples strolled through the warren of alleyways and tunnels, now brightly illuminated by cheery shop windows and klieg-like streetlamps.

But the most striking metamorphosis wasn't cosmetic: the Nervión River no longer stank. With the sludge-spewing factories gone and sewage treatment plants installed, the river began to heal itself. It may not be as blue as the Danube (the color today is more like a rusty green), but within an hour of my arrival, I spotted a lone sculler in a red jersey, gliding by a pair of cormorants.

The cleaner water, however, hasn't necessarily brought more tourists upriver. Despite a host of tourist information centers, including a glass shed outside the Guggenheim staffed with professional guides and a rainbow of color brochures, Bilbao remains very much a one-attraction town.

On a cloudless Sunday morning, the Museo de Bellas Artes — with important works by El Greco, Francis Bacon and Eduardo Chillida — was nearly empty, despite a 2001 expansion and being just a quick stroll from the Guggenheim. Maybe that's why the museum closes at 2 p.m. on Sundays. (At least it was open. The city — restaurants, grocery stores, cafes — shuts down on Sundays; everything, that is, except the Guggenheim.)

The Maritime Museum, which traces the city's port and sailing history, was completely deserted, save for the bored-looking woman at the ticket counter. Even the Moyúa neighborhood next to the Guggenheim, which should have benefited from the Bilbao Effect most acutely, is far from tourist ready. There's one postcard store across the street and a couple of hip restaurants nearby, but this residential district is otherwise filled with featureless stucco apartments, five-and-dimes and plain bodegas. A clutch of art galleries have sprung up along Calle Juan Ajuriaguerra, but its proximity to the Guggenheim is merely coincidental.

“There's no art market in Bilboa,” said Javier Gimeno Martiñez-Sapiña, who owns the year-old photogallery20. “I don't think the Guggenheim has helped. It's still very hard for local artists to sell art here. They have to go to Madrid or Barcelona.”

No wonder many guidebooks still devote as many pages to the Guggenheim — reprinting floor plans, offering tips and expounding on the museum's design — as they do the rest of Bilbao. On paper at least, Bilbao seems to have it all: world-class museum, fine Basque cuisine, a rollicking night life and lots of shopping. But like the new bike paths that were rarely used during my visit, the city lacks the critical mass of attractions to take it from a provincial post-industrial town, to a global cosmopolitan city. And in the meantime, it is losing the shabby edge that gave the city its earlier appeal.

The concentration of first-rate architecture is astounding, even without Gehry's titanium masterpiece. But architecture alone does not a city make. Bilbao is all dressed-up, but hasn't figured where to go.

“Our local culture still hasn't integrated with the Guggenheim,” said Alfonso Martínez Cearra, the general manager of Bilbao Metropoli-30, a public-private partnership that is guiding the city's revitalization. “This is still an industrial city.”

The disconnect between Bilbao the brand, and Bilbao the city was on display one Saturday night, when the narrow streets of Casco Viejo were once again packed with young bar-hoppers. The smell of marijuana wafted from a crowd outside a bar on Calle de Somera. In the group was Ikel, a 22-year-old studying to be an engineer, like his father.

“I've never been to the Guggenheim,” Ikel said between puffs, as mechanical street cleaners starting scrubbing beer and urine from the cobblestones. “It's for tourists.”

VISITOR INFORMATION

GETTING THERE

Flights from New York to Bilbao, with stopovers in either Paris or Madrid, start at about $700 for travel next month on a number of airlines, including Iberia. From Bilbao airport, a taxi to the city center is about 25 euros ($35 at $1.40 to the euro).

Most attractions can be reached by foot, though the futuristic metro system is an attraction in itself. A BilbaoCard, for unlimited metro and tram rides, plus museum discounts, starts at 6 euros for a day and can be purchased on the city's tourism Web site (www.bilbao.net/bilbaoturismo).

WHERE TO STAY

Iturrienea Ostatua (Santa Maria Kalea 14; 34-944-16-15-00; www.iturrieneaostatua.com) offers Old World charms and exposed oak beams in the heart of Casco Viejo, with rates staring at 60 euros. Ask for a room with a balcony overlooking the cobblestone street.

Gran Hotel Domine Bilbao (Alameda de Mazarredo 61; 34-94-425-33-00; www.granhoteldominebilbao.com) is across the street from the Guggenheim and has 145 modern rooms starting at 140 euros a night. The rooftop terrace offers great views of the museum and surrounding hills.

Hesperia Bilbao (Campo Volantín 28; 34-94-405-11-00; www.hesperia-bilbao.es) is a trendy newcomer, next to Santiago Calatrava's footbridge over the Nervión River, and has 151 boutique-style rooms starting about 90 euros.

MUSEUMS

Guggenheim Bilbao (Abandoibarra 2, 34-94-435-90-80; www.guggenheim-bilbao.es). Open 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. every day except Monday. Admission is 10.50 euros.

Museo de Bellas Artes (Museo Plaza 2, 34-94-439-60-60 www.museobilbao.com). Open Tuesdays through Saturdays, from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m, Sundays from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. Closed Mondays. Admission 5.50 euros.