LET'S free associate. If I say Capri, what comes to mind? Glamour, gorgeous views, ritzy shopping — the uninterrupted leisure of la dolce vita. And what if I say Graham Greene? Troubled faith, espionage, unforgiving, “cinematic” realism, seedy characters in sordid places. “Greeneland” can be thrilling on the page, but not many of us would want to go there on vacation.

In other words, there's good reason to assume that the 20th-century British novelist and the sparkling island in the Bay of Naples are mutually incompatible, that the two should never be linked in the same sentence. Greene, typically succinct, had this to say about Capri: “It isn't really my kind of place.”

Once a second home to Roman emperors, it's now a tourist destination, and Greene, one of the most traveled writers of all time, was temperamentally unsuited to tourism: The notion of traveling for fun wouldn't have occurred to him.

And yet he bought a small house on Capri in 1948 and kept it for more than 40 years, returning for short visits, mostly in the spring and fall, until the very end of his life, when he became too ill to travel. The house, Il Rosaio, was a rare constant in Greene's restless existence (“one of nature's displaced persons,” Malcolm Muggeridge called him). In 1978, Greene was made an honorary citizen of the town of Anacapri, and in a brief speech on the occasion, he gave the obvious explanation for his biannual pilgrimage to an island that wasn't at all to his taste: On Capri, he said, “in four weeks I do the work of six months elsewhere.”

Case closed. Writers must sit alone at a desk and write — that's the only way the books get written, and Greene wrote a great many, including 26 novels. “The End of the Affair” (1951), “The Quiet American” (1955), “Our Man in Havana” (1958), “A Burnt-Out Case” (1961), “Travels With My Aunt” (1969) — portions of all of these were written in the bare, whitewashed study at Il Rosaio. If you need further proof that the connection between Greene and Capri was essentially utilitarian, consider this: Though he wrote copiously while he was on the island, dutifully turning out his minimum daily quota of 350 words (“One has no talent,” Greene perversely insisted, “I have no talent. It's just a question of working, of being willing to put in the time”), he never once used Capri as material for his fiction.

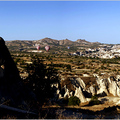

But if you go there with his books on the brain, you'll discover the moment you arrive that Capri and Greeneland are not necessarily so far apart. From a distance, as the ferry crosses the wide bay, with Naples and Mount Vesuvius at your back, the island promises the delights of a Mediterranean paradise: dramatic limestone cliffs capped with a thick canopy of trees; a cheerful splattering of houses, white and pastel, climbing up steep hills from a harbor crowded with sumptuous yachts.

As the ferry docks, the brute logistics of day-trip tourism take over: thousands and thousands of bodies flow in and out of the port every day of summer, disembarking in the morning only to trudge back up the gangplank, sweaty and tired, late in the afternoon. The pier, with as many as half a dozen ferries swallowing or disgorging passengers, is packed alarmingly tight.

Greene had captured the feel of this kind of human tide a decade before he first came to Capri. In the opening pages of his masterpiece “Brighton Rock” (1938), he described the holiday crowds arriving in Brighton, 50,000 of them down from London for a day at the seaside, “stepping off in bewildered multitudes into fresh and glittering air.”

The air in the Marina Grande is glittering, yes, but not fresh — diesel and sunblock perfume the tawdry scene. Get out as quickly as you can — the title of Greene's second volume of autobiography springs to mind: “Ways of Escape” (1980) — and avoid centers of population until the evening, when the day-trippers have departed.

The vast majority of tourists take the funicular up to the town of Capri, where the modest, winding streets have been hijacked by high-end retail: Prada, Tod's, Bulgari, Gucci. Imagine Rodeo Drive squeezed into the narrow lanes of an Italian hill town and swept by a surging stream of visitors in sneakers and knapsacks, a ululating Babel that circulates in and out of the main piazza like a video on a playback loop.

Others take stubby orange buses and convertible taxis across the sheer face of a cliff and up and around Monte Solaro to Anacapri, the quieter of the island's two towns. It, too, has a touristy pedestrian shopping street, noticeably less chic, that peters out as it wends westward. Piazza Caprile, the small, dusty square closest to Greene's house, could be the center of any ordinary Italian village. No trace here of either la dolce vita or the day-tripping masses, only an optometrist, a fruit and vegetable store and a betting parlor. Old ladies with canes are dressed in black, woolly tights on their swollen legs; children, running home for lunch, wear smocks; grizzled men stand in doorways in groups of two and three, smoking. A spreading olive tree promises that the piazza is as it was and will be.

The street down to Greene's house narrows past the bakery, the hardware store and the self-service laundry. Bougainvillea spills over the whitewashed walls of villas, a cascade of bright flowers, cactus crowning a doorway. Around a bend, a hazy slice of the Tyrrhenian Sea in the distance is just a shade darker than the cloudless sky. Palm leaves rattle in the breeze, and from farther away comes the sound of unhurried construction. Around another corner is Il Rosaio. Near the wrought-iron gate, a marble plaque erected in 1992 by the Lions Club of Capri informs visitors (in Italian) that this was the residence of Graham Greene, honorary citizen of Anacapri. Two loud American women march by, huffing from their hike; they pass without a glance at the house or the plaque — just about the only visible trace of Greene left on the island.

At the bookstore in Capri, not one of Greene's novels is for sale, either in English or in Italian. Ask for his books and you'll be handed a copy of Shirley Hazzard's delightful, utterly unsentimental memoir, “Greene on Capri” (2000). Ms. Hazzard's affection for her cantankerous friend and his “unquiet, unappeasable spirit” allows her to be at once sympathetic toward a writer she admires and clear-eyed about his prickly personality.

Ms. Hazzard and Greene shared a favorite restaurant in Capri, da Gemma. “The unadulterated simplicity of Gemma's restaurant was a stable factor that helped make the island agreeable to Graham,” she writes. “Like many restless people, he preferred to find his ports of call unchanged.” The restaurant's namesake, Gemma, died in 1984 (and Greene took part in the funeral procession), but her family still runs the restaurant, which remains popular.

Habitually frugal, Greene liked to eat early and catch the last bus back to Anacapri — to spare the cost of a taxi. Much more pleasant to stroll back to the piazza for coffee and a grappa at the Gran Caffè (where Shirley Hazzard first met Greene) and watch the flow of passers-by. It's a place to see and be seen — not even Greene could resist the urge to scope out individuals of interest: He claimed to have spotted in the piazza a “handsome white-haired American gangster, one of Lucky Luciano's men, spending the quiet evening of his days.” Ms. Hazzard assures us that “Graham cared nothing for fashionable life,” but if you enjoy ogling people, the piazza at night is an ideal spot for it. If you need to justify your voyeurism, scan the crowd and say to yourself that you're studying Greene's method. He once told an interviewer, “When I describe a scene, I capture it with the moving eye of the cine-camera rather than with the photographer's eye — which leaves it frozen.”

It's true that enjoying a nightcap and a peek at the pastel parade does seem a long way from what the critic James Wood calls Greene's “Catholic writings” — and from his strenuous and mostly iconoclastic left-wing politics. But Capri is a long way from the cares of the world and besides, the island's tidy Baroque church, Santo Stefano, where Greene occasionally attended Mass, is being restored, the ceiling obscured by a canopy of scaffolding.

If a Mediterranean vacation seems like the wrong occasion to wrestle with Greene's favorite themes, at least one can trace his wanderings around the island. According to Ms. Hazzard, “natural beauty had erratic claim, only, on [Greene's] attention;” he was “a man largely unmoved by visual experience.” And yet his daily routine usually included an afternoon walk, often to the Belvedere Mígliera, a half-hour's amble along a pleasant track through the outskirts of Anacapri, past meticulously tended vineyards, to a lookout perched vertiginously 300 yards above the empty sea.

A walk on the opposite end of the island leads up to the sumptuous Villa Jovis built by the emperor Tiberius. Ms. Hazzard tells of an expedition there with Greene, climbing up though the ruins and looking out over “some of the loveliest scenery on earth.” In the distance, offshore from Positano, are Li Galli, tiny, rocky islands, one of which belonged at the time to the Russian dancer and choreographer Léonide Massine (after Massine's death the island was bought by Rudolph Nureyev). Greene remarked, “the place looks idyllic, but might be hell.” Ms. Hazzard dryly notes, “Graham was inclined to suspect — in some moods, perhaps to hope — that most idylls might be hell.”

After three days on Capri, I came to the conclusion that one can best summon up Greene by defying him, by matching his notorious belligerence with a stubborn commitment to all the pleasures he had difficulty embracing. Rent a little boat and circle the island, soak up the beauty (the big tour boats are cheaper, but if you spoil yourself, you'll enjoy the privacy and the freedom to anchor where you like to swim and sunbathe). Stroll out in the evening to the Arco Naturale, and stop for a glass of prosecco at Le Grottelle (Greene's third favorite restaurant, according to Ms. Hazzard). The secluded trattoria's tables are perched on a terrace 150 yards above the sea, with a view of the Sorrentine peninsula, some three miles away. As the sun sets behind you, it lights up in pink a bank of clouds on the horizon. Across the water, the village of Praiano is a dusting of white on the distant promontory. Later, if you stay for dinner, the darkened sea is mapped out by a constellation of fishing boats. A heavenly idyll.

VISITOR INFORMATION

GETTING THERE

Ferries and hydrofoils offer regular service to Capri from Naples, Sorrento, Ischia and other ports. For more information, see www.capri.com.

Where to Stay

It is never cheap to stay in a hotel on Capri. If you're after la dolce vita, some five-star hotels will set you back about 400 euros, or about $550 at $1.38 to the euro, for a double room in the high season.

Capri Palace Hotel and Spa, Via Capodimonte, 2b, Anacapri, (39-081) 978-0111; www.capripalace.com. The starting rate for a double room is 420 euros.

Grand Hotel Quisisana, Via Camerelle, 2, Capri, (39-081) 837-0788; www.quisi.it. Double rooms start at about 340 euros.

Hotel Excelsior Parco, Via Provinciale Marina Grande, 179, Capri. (39-081) 837-9671; www.excelsiorparco.com. Less expensive, less luxurious and perfectly pleasant (though noticeably understaffed). Doubles start at around 290 euros.

WHERE TO EAT

Graham Greene had three favorite restaurants on Capri, according to his friend Shirley Hazzard. Dinner for two and a bottle of wine will cost about 75 euros.

Da Gemma, Via Madre Serafina, 6, Capri; (39-081) 837-0461.

Settanni, Via Longano, 5, Capri; (39-081) 837-0105.

Le Grottelle, Via Arco Naturale, Capri; (39-081) 837-5719.

READING

In addition to Shirley Hazzard's memoir, “Greene on Capri” (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000) and Norman Sherry's “The Life of Graham Greene” (Penguin, 2004), there's a solid new book about Greene's fiction — “A Study in Greene,” by Bernard Bergonzi (Oxford University Press, 2006).