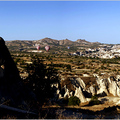

Some of the thousands of sandstone pillars of Wulingyuan.

I AM in a deep, deep tunnel, die-straight and dark and two miles long, a fingernail of faraway brilliance at its mouth brightening every second until, with startling suddenness, it is daylight. Ahead of the car are scores upon scores upon scores of mighty towers, climbing endlessly into the foggy sky, like some surreal and unexpected ruined city. It is a sight utterly to astonish the unprepared, akin only perhaps to the moment when a Midwestern soybean farmer is flushed out of the Lincoln Tunnel into the canyons of Midtown Manhattan.

But this is not New York. This is central China, and a remote part of the mountains of northwestern Hunan province, until lately seldom visited and indeed until 50 years ago barely even settled. The tunnel is brand new, built last year for the equivalent of $200 million, and the towers to which it leads are not skyscrapers — well, they are, though not made of steel and glass, but natural, of a buff Cretaceous sandstone, and topped with clinging pine trees. There are well over 3,000 spires, and they make up what the United Nations 15 years ago declared to be one of the most remarkable geomorphological spectacles existing on our planet.

The Wulingyuan National Park is magnificent enough — for its topography, for its rare plants and trees and for its stupendous (though panda-free) fauna — that it has been officially designated by Unesco as demanding protection for the benefit of all mankind. Once word of this designation became known, though, all mankind decided it wanted a look-see — and armies of tourists began to descend on the wilderness of northwestern Hunan, trampling the trails, muddying the ground and causing deep anxiety among those charged with managing the region’s treasures.

So far, only a smattering are Westerners. But the Chinese themselves, who with their newfound freedoms and prosperity (and cars and superhighways and cellphone towers) are fast discovering their country as never before, have all of a sudden, and in their millions, discovered Wulingyuan.

The manner in which that discovery is manifesting itself speaks volumes about the way the world can and should be dealing with its most precious places.

The deliciously intricate geology of China — basically an immense tectonic plate endlessly tormented by titanic collisions with the neighboring plates that bear India and Australia — is of course responsible for both the fabulous complexities and the extreme isolation of Wulingyuan. Sixty million years ago there were tropical seas there; sometimes they were deep, leaving soft and fossil-rich limestones, sometimes shallow, leaving hard beach-sandstone. Then the land rose under tectonic pressure, and the weathering of the limestones and sandstones proceeded in that peculiar way that is called, after a geologically similar area in Slovenia, karst. The limestones dissolved over millions of years into fissures and sinkholes and immense caves, the sandstones cracked into knife-edged pillars, some of them like needle-shaped mesas, fully 1,000 feet high.

Tourists come to this increasingly accessible corner of China to see both — although most I spoke to said they had come for the landscape of towers, which looks uncannily like the ink-and-paper drawings that for centuries have presented a defining aspect of classical Chinese art. Yet there is a difference: the art is fanciful, the imagined landscapes of the creative mind; the geology of Wulingyuan has produced more than 100 square miles of landscape that is very much the real thing, however fantastic it might at first appear.

As I drove there from the immense and grubby city of Chongqing, a hard day’s journey, I confess to having fairly low expectations. The weather was unpropitious, to say the least: it was raining hard, and a stiff westerly gale was blowing the stain of city pollution almost to the fringes of the park. I had been to countless other Chinese tourist sites before and had winced at how often the authorities seemed to render their charges into Asian versions of Gatlinburg or Blackpool or, at best, Disneyland.

But at that first sight of those soaring towers at the tunnel mouth, everything changed. (As did the weather: as if by an edict of the gods the wind eased, the rain softened until it had become no more than mist, and the summits of the pillars became wrapped in fronds of cloud as delicate as skeins of silk.)

The scenery in Wulingyuan turns out to be so immense and impressive, and yet so geologically frangible, that it seems positively to demand to be cared for. Like the Grand Canyon and Monument Valley, the huge forests of pillars stand foursquare against the distant blue hills, announcing themselves to be the very treasures that Unesco declares them to be. At every twist and turn of the road there is a view to make one gasp.

In terms of astonishment I found myself saying time and again, as I gaped from cliff-edge and bridge and viewing tower: This is as great as the Great Wall. And all the while I had to remind myself that Wulingyuan had been made by nature for China, and though it looks in places almost too perfect and carefully hewn to be true, not made, like the wall, by politically motivated man.

Yet politics has contributed significantly to turning Wulingyuan into an important way-station for the modern Chinese visitor. A senior Communist soldier named He Long — who was from the minority Tujia ethnic group and so was particularly venerated for his loyalty to the Maoist cause — happened to come from this region of Hunan. During the Civil War of the 1930s he took refuge in the canyons and remote river valleys, venturing out from time to time to wreak havoc on any nearby Republican forces.

When the war was over and the People’s Republic was declared in 1949, Marshal He became a national hero, and the theaters of his battlings entered the geography of the national epic, along with the route of Mao Zedong’s Long March and the details of the capture of Beijing. So a trickle of visitors started in the mid-1950s, all ardent pioneers taking part in a patriotic pilgrimage. A gigantic bronze statue of Marshal He was erected, looking suitably heroic on a cliff edge, a quiverful of 600-foot sandstone spears bristling up from the depths behind him. To touch the hem of the marshal’s cloak in Wulingyuan is, for many, the realization of an immense ideological ideal.

But now it is mostly about tourism, and pleasure. In the late 20th century, a rapidly changing China realized that it had in Hunan a scenic amazement on its hands. It already had the Great Wall and Guilin and the terra-cotta warriors of Xian. Now, within easy reach of Shanghai and Guangzhou and not too far from Beijing, it had a gem of a place, hitherto unknown, unseen, scenically unforgettable, culturally impeccable and politically just the ticket. The central government declared it the country’s first National Forest Park in 1982; Unesco awarded it World Heritage Site status in 1992, and then, in 2004, declared it one of the world’s GeoParks, a classical and world-class demonstration of remarkable geology. Whereupon the floodgates opened, and all China began to pour in.

A brand-new domestic airport has just opened in Zhangjiajie City, 20 miles away; a new road will connect the park to Chongqing, which has a municipal population exceeding 30 million and lies just 300 miles to the west and will soon not take a long hard day to drive, as it had taken me; a four-lane superhighway has just been opened to the huge city of Changsha, three hours off; four flights daily connect to Hong Kong. There are even more flights connecting to Seoul, and Wulingyuan is being heavily advertised on South Korean television.

I had my fears. I have been on the Great Wall on a stifling summer’s day; I have seen Kyoto’s Philosopher’s Walk in mid sakura season, and I have known Venice during the Biennale — and so I have seen the third circle of tourism hell, and I fret over its potential for spreading. But now that I have been there, I have little hesitation in applauding the Chinese for managing this most extraordinary of sights — using a mixture of ruthless discipline and tender care. Wulingyuan, it seems to me, works. This truly world-class spectacle is remaining, if barely, uncrowded and unruined by the immense battalions who now quite understandably wish to see it.

High technology and high cost control the crowds. A truly bewildering array of entry charges — all of them displayed on a board at the park entrance that has to be fully 20 feet long to accommodate their various permutations — comes down to one reality: it costs a bald 248 yuan to get in. That is about $32, a little more than an average week’s wages in China.

Once inside there are more charges: to ride a bus or the aerial cableway (Austrian-built, installed last year, and breathtaking as it swings between and above the sandstone pillars); to take a three-car glass-walled elevator bolted up the side of one of the tallest pillars; to visit the caves (which are privately owned by one of Deng Xiaoping’s grandsons); to circle an artificial lake owned by a Hong Kong investment firm. There is some rather tame whitewater rafting, too, 130 additional yuan for an experience not much more exciting than tubing on the middle reaches of the Susquehanna.

All things considered, a Chinese family visiting Wulingyuan can easily spend two months’ pay in a single day. A foreign family will perhaps feel less pain, but because of the high prices all feel a sense of privilege once inside — which is a feeling, I am fast coming to think, that responsible 21st-century tourism should perhaps engender.

Moreover, the gatekeepers know exactly how many are inside the park at any one time, and they have the power to shut would-be visitors out, which might seem harsh, but to those trapped in a heaving summer scrum on Piazza San Marco or inside the Forbidden City, it is the kind of decision that would probably seem a sensible relief.

The disadvantage is that the park’s cost-free walkways — most notably that along a three-mile canyon close to the lower entrance — can be unbearably crowded, with long lines of strollers (and the unfit and the elderly in bamboo sedan chairs) creating an ugly and noisy congestion. As elsewhere in Wulingyuan, there are monkeys aplenty for such mobs to see and feed (illegally); but if there really are cloud leopards and pangolins and all the other animals and birds for which this reserve is said to be famous, the commotion along the Golden Whip River Canyon has clearly sent them all scurrying off into the forest.

As most Western visitors would dearly like to do, I suspect. The park regulations do not seem to allow overnight camping; but they do permit wandering on half-defined trails, and I imagine that most outsiders who get to the park would have little interest in paying obeisance to Marshal He, but would relish the chance, especially if the weather is good (and springtime, when the cherry and plum trees are in full blossom, is splendidly cool and misty) to walk, and commune with that rarest of treasures — Chinese nature.

And there is one superb benefit for doing so, I discovered as I trekked up the 3,000 stone steps to a temple site on top of one of the mountains. According to signs posted every half mile or so, there is No Smoking, anywhere inside the park. I didn’t see a single soul lighting up — and in China that is quite remarkable.

The consequence is that in Wulingyuan, not only are the peaks tall and the waters clear, the birds in full song and the flowers in bloom, but the atmosphere is — as almost nowhere else in China — well nigh perfectly clear. And that is perhaps the very best reason to go. Here you can breathe fresh air, something that in today’s China is the most precious of finds, and a very great delight.

VISITOR INFORMATION

Wulingyuan National Park, about 860 miles southwest of Beijing, covers more than 100 square miles in Hunan Province and encompasses four major scenic areas: Zhangjiajie Forest Park, Yangjiajie Scenic Spot, and Tianzishan and Suoxiyu Natural Resources Reserves. A tour of several attractions takes about three days.

A general-entry ticket, good for two days, costs 248 yuan ($31.90 at 7.77 yuan to the dollar) at the park gates. Separate tickets are required for cable cars, lifts and access to some areas. Within Suoxiyu Reserve, for example, prices include 130 yuan for rafting on the Maoyan River, 65 yuan to visit Longwang Cave (Dragon King Cave) and 62 yuan for Baofeng Lake.

The most convenient airport, Lotus Airport (Hehua Airport) in Zhangjiajie City, about 23 miles from the park entrance, is served by daily flights to and from several major Chinese cities. The two-hour flight from Beijing on Air China or Hainan Airline costs 1,470 yuan , with discounts available during the off-season. Flights from Hong Kong on China Southern Airlines arrive twice a week. A taxi from the airport to the national park costs 80 to 100 yuan , with most drivers open to negotiation.

There is no direct bus to the park, but buses run from the airport to the bus station in downtown Zhangjiajie City, and from there to the park every 10 minutes from 5 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. Traffic at the park gate is usually light, with long lines expected only during peak holiday periods, such as October and the first week of May. Shuttle buses within the park connect major sites.

Hotels within walking distance of the park gates include Hunan Xiangdian International Hotel (86-744-5712999), with mountain-view rooms starting at 480 yuan ; Hunan Pipaxi Hotel (86-744-5718888), in the courtyard style of the local Tujia people, with rooms from 440 yuan ; and Best Western Premier Zhangjiajie (86-744-5669888), the best-appointed of area hotels, with rooms from 800 yuan. To get the lowest rates, book through a travel agent.

Most visitors have breakfast and dinner at their hotels and eat lunch inside the park, where restaurants are easy to find at popular tourist sites but rare in less visited areas. The most popular fast-food places in the park are Tianzi Fastfood, with three locations, (86) 744-5618588, (86) 744-5617888 and (86) 744-5617777, and Tianqiao Fastfood, (86) 744-5719226. These offer buffets as well as regular meals, including such local delicacies as wild fungus, pine mushroom, sweet corn on the cob, kiwi, partridge and wild boar. Locally run restaurants are also found in the park.

In Zhingjianjie, try Xiang Li Ren Jia (Second Floor, Tianmen Clothing Mall, Huilong Road, Zhangjiajie City, 86-744-8297977), featuring local sour and spicy Hunan-style dishes. By LIN YANG