THE border towns of Columbus, N.M., and Palomas, Mexico, lie just three miles apart, but that short distance — what you might drive to the supermarket, say — encapsulates a world of difference.

Columbus is sparsely built and sparsely populated: fewer than 2,500 people, living in trailers, RVs and modern ranch homes in the desert, with low, dry scrub never more than a rabbit’s hop away. Each downtown block contains at most four buildings, painted yellow, blue or pink, and between them are dusty lots. From the outside, it can be hard to tell whether anything — three cafes, a library, the chamber of commerce — is open, so still is the air and so empty are the streets. It’s like a well-tended house awaiting its owners’ return from vacation.

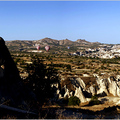

By contrast, Palomas is dense and lively. Concrete buildings cluster around the port of entry into the United States, and street vendors sell decorative saddles and paletas (similar to Popsicles) to American tourists. Errant mariachi bands patrol the streets, and at noon men sit under shady trees in a park to hide from the sun. When it rains, the streets, many of them dirt roads, flood badly, and shoeless children appear even more pitiful as they beg for pesos. Farther from the border, the houses are frequently unfinished gray concrete shells with “For Sale” signs hanging in glassless windows. A few kilometers out and you’re back in the desert.

This border zone might not seem like a pleasant place for any traveler, frugal or otherwise, to spend a few days, yet it appealed to me for two reasons. First, with immigration a hot political topic, I wanted to witness life as it’s lived on the front lines. Second, Columbus is home to Martha’s Place, a bed-and-breakfast with raves from TripAdvisor.com (“Charming & Comfortable,” “An Oasis in the NM Desert”) and an eminently affordable room rate: $40 a night, since I was staying three nights. Most nightly rates are $60 to $70.

Just after 5 p.m., following a daylong drive from Odessa, Tex., during which the front wheels of the Volvo made a worrisome sound like a helicopter’s whump-whump-whump, I arrived at Martha’s Place (204 West Lima Avenue, 505-531-2467; www.marthasplacenm.com). It is a wide adobe-style building, with balconies and a homey interior that lived up to the Web reviews. Martha Skinner, a real estate agent and the town’s former mayor, showed me to a pale-blue bedroom and gave me my first tutorial in Columbus life: If I wanted to eat, she said, I’d need to do it soon — all the restaurants close at six o’clock. Fifteen minutes later, I was tucking into a “wet” burrito ($7), full of luscious shredded beef and smothered in red chili sauce, from the Pancho Villa Cafe (327 Lima Avenue, 505-531-0555).

The restaurant’s name, it turns out, comes from the town’s history. The next morning, I visited the Columbus Historical Society Museum (505-531-2620), in an old train station full of archival photographs, old newspapers and other artifacts. There I met W. Lee Robinson Jr., a talkative, balding man who said everyone calls him Radar because he looks like Radar from “M*A*S*H.” Back in early 1916, Radar explained, Mexico was in upheaval, and Pancho Villa, a revolutionary general, was feuding with the federal government in Mexico City. This conflict might have stayed within Mexico’s borders, except that Woodrow Wilson decided to end his support of Villa and back Mexico City instead. In revenge for this slight, Villa sent his forces across the border on March 9, 1916, to raid Columbus. They burned buildings, looted businesses and killed 10 citizens and 8 soldiers before being routed.

The attack left Columbus with an acute sense of the border, its identity forever intertwined with Palomas’s. For decades, residents have been freely crossing into Mexico for taco dinners, duty-free cigarettes and liquor, and even visits to the dentist. But they’ve also become hyper-aware of their counterparts — the Mexican immigrants, illegal or legal, who cross over into America, some carrying drugs, others dreams. And whatever their feelings about the border, they seem to understand that Columbus would not exist, either in history or today, without Palomas — and vice versa.

That strange symbiosis has gotten stranger in recent years, with post-9/11 security measures and anti-immigration policies making the journey from south to north tougher.

And it may get harder still. One evening, I drove out to look at what is known simply here as “the fence,” the controversial barrier being built between the two countries. My guide was Radar from the historical society, who also happens to be a radio operator for the Minutemen Project (www.minutemanproject.com), a border-watch group seeking to stanch the flow of illegal crossings.

As a light rain fell, Radar explained that his group had developed a harmonious relationship with the United States Border Patrol — the Minutemen spot Mexicans crossing illegally, then pass the location to law enforcement. I was skeptical, but when we neared the fence, he chatted amicably with several Border Patrol officers and they let us through without a problem.

The fence, it turned out, is far from finished. There was a concrete foundation that went down six feet (too deep to tunnel under), steel pylons that soared 15 feet (too high to jump from), and X-shaped beams constructed from railroad ties (too tough to drive over). But its various sections each run for only a few hundred feet.

We walked to one end and Radar pointed across the border, to an unfinished concrete house surrounded by garbage. “Look how they live!” he said, disgusted.

The rain fell harder, and as we drove away through the mud, his words rung in my ears and I had to question his remark. After all, for many people in Palomas, the town is hardly home, hardly worth keeping up — just a stopover on the way to America.

One day, just before lunch, I set off for Mexico. The well-paved road to the border was barren most of the way, but ended in a shopping center that included a Western Union, a Family Dollar supermarket and a duty-free liquor store. The Mexican border guards waved me through, and I was in Palomas.

Compared with Columbus, the roads were rougher, the buildings denser and the people poorer. The Pink Store (Zaragoza 113; 505-531-7243), however, shone like a beacon of affluence. It is the town’s prime tourist attraction, a kitschy restaurant and handicrafts shop, and amid tin crucifixes, vividly painted mirrors, carved wood animals and several other gringos, I ate O.K. chili and drank a slightly better margarita (no extra charge, with a coupon). Lunch cost $7.15 with tax, but I left craving more. Luckily, this was Mexico, and down the side streets were taco and torta stands. A pair of tacos de barbacoa cost $1.25 and were a million times better than that chichi chili.

The sun was hot and high in the sky, but I walked around Palomas anyway, curious about who I’d meet. One guy approached me, asking if I wanted “coke, whiskey, weed, girls.” (I declined.) At a brand-new hotel, the owner asked me to say hello to Martha Skinner; he is her dentist. At a shaded park, another man told me he was on his way to Phoenix, Ariz., to do roofing work in the 120-degree heat.

I kept returning to Palomas over the next couple of days, not only to fill my belly with inexpensive food (Gámez, on Cinco de Mayo Street, had excellent grilled chicken) and my car with inexpensive gasoline ($31.25 for a full tank at Pemex, about $8 less than in Columbus). But life here was also more vibrant — and didn’t shut down at 6 p.m.

Once, I stopped in at a La Reina de Michoacán ice-cream parlor where I had a fantastic guava paleta ($1) and met an older man carrying a fat pet lizard. While he let it run around his table, he told me in awkward English that he used to work illegally in San Diego before being deported. Now he was holed up in Palomas, biding his time till he could cross the border again. As he pronounced his name — Charles, not Carlos — I could sense his pride in simply having lived on the other side.

When I drove back to New Mexico that night, the United States border guards pulled me over for questioning — apparently, they don’t see many New York license plates and even fewer visa-filled passports. They were friendly, but still, my heart beat faster, and I tried to imagine how a foreigner must feel. A single wrong word, a misunderstood cue or bureaucratic slip-up might be enough to strand you in Mexico, three miles from the sleepy town that might be your gateway to a new life.

After several minutes, the guards handed me my passport and sent me on my way. The Volvo wheezed into gear, and I returned to my pale-blue bedroom in someone else’s house.

Next stop: Colorado.