At Fundació Joan Miró, a show of works by Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen.

IT was a cool spring day at the foot of La Rambla, Barcelona's famous — and famously overrun — main promenade. I had been strolling under the freshly leafed plane trees, but now the sky threatened rain, and the crowds were growing wearisome. It was the perfect time to duck into the darkness of the Centre d'Art Santa Mònica. Inside the museum, a former convent, the bustle of the city falls away.

On the dim, vaulted main floor I found seven large screens that divided the space irregularly. Upon each was projected the video image of a luminous white wall and a barred doorway, through which I glimpsed a walkway and summer foliage.

Entitled “Lugar de Silencios,” the piece was a collaboration between the Barcelona artist Montserrat Soto and the poet Dionisio Cañas. Portly in a sweater and long gray hair — a portrait of the artist of a certain age — Mr. Cañas appeared in the video doorways from time to time, deep in thought amid crunching footfalls. Breaking the silence, he proffered snippets of poetry: “No time, no time, no time./No time for coffee,/no time for donuts,/no time for The New York Times.”

Barcelona can be overwhelming for visitors, and the stillness was a welcome break from a forced march of medieval alleyways, tapas and must-see attractions. But as my wife, Nina, and I discovered, Barcelona's art scene, in its breadth, its internationalism and above all its depth, is hardly a respite.

For the visitor, art in Barcelona mirrors the city's charming jumble. “It's a place you can walk, a city for flaneurs,” said Manuel Borja-Villel, director of the Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona, called Macba. “You can lose yourself here.” Indeed, when we visited, the museum featured installations by the Canadian artists Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller. The cluttered, moody environments evoke the rooms of the mind, where memory and nostalgia give way to darker dreams.

Installations like “The Dark Pool,” a chaotic stage set shot through with snippets of sound triggered by visitors' motion, reminded me of an old bar in the surrounding El Raval neighborhood — the kind of place where dark casks of vermouth line the walls, and the air is blue with cigarette smoke and sharp with salty fish. My favorite, which I'm sure I'll never find again: a timeless joint named Montse's, vanished down a narrow street on an exploration measured in wine and olives.

Places like that, where vermouth seeps out of ancient tarnished pipes, are not the reason most come to Barcelona. But if you stumble into them, they're what you remember most vividly.

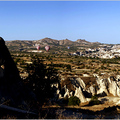

It's the same with art. Over everything loom the giants: Picasso, Dalí and Miró. Each spent formative years in and around Barcelona, and each has a museum dedicated to his work in the city. Of them the Fundació Joan Miró is the most striking. Not only is its location magnificent — it is set on the leafy slope of Montjuïc, overlooking Barcelona's jumble — but the collection is a comprehensive and definitive look at the artist's work. The airy space is filled with the echoes of laughing students, a rambunctiousness invited by the tense motion in Miró's canvases. (When we visited, the Fundació also featured a show of the bold, bent forms created by Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, which seemed an ideal pairing with Miró's work.)

The Picasso-Dalí-Miró trinity connects 20th-century Spanish art with its historical antecedents. The Museu Picasso is particularly good at demonstrating this: on 58 canvases, Picasso reinterprets Velázquez' 1656 “Meninas,” enlivening it with cameos by his dachshund, Lump, and evoking, around Canvas 23, the sinking my-5-year-old-could-do-that philistinism Picasso is famous for.

But it is telling that Picasso's and Dalí's best work is not here. The bulk of their careers were spent elsewhere, and their masterpieces reside in places like Madrid, Paris and New York. “In those cities,” Mr. Borja-Villel said, “art is displayed in a colonial way. But there is no sense of empire here. Barcelona is a capital with no country. It has nationalistic pride but no trophies.”

Free from the ponderous shadows of iconic masterpieces, Barcelona's art scene is broad and eclectic. “It's a rich cultural space, but fractured,” said Josep Ramoneda, the founding director of the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona. The center opened its doors in 1994 to provide a focal point for creative energy in the city. “There were many groups doing things here,” Mr. Ramoneda said, “but they weren't connected.”

During the Franco government, expression was tightly controlled. Spanish art had skipped a generation by the time democracy was restored in 1978. “Modernity did not exist here,” Mr. Borja-Villel said. “We went from Franco straight to postmodernism.”

The Macba building is an impressive space that combines well-thought-out exhibition halls with airy public spaces. It is fronted by a courtyard that resembles a skate park: university students gather there amid the clatter of plywood decks and bustling outdoor cafés.

This is quite a change for a neighborhood once synonymous with port city seediness. “Twenty years ago,” Mr. Borja-Villel said, “you could not come here with a clean shirt.” Barcelona's revitalization was initiated with the 1992 Olympic Games. The early stages of its makeover, chronicled in dreamlike black-and-white by the photographer Manolo Laguillo and on display at Macba when we visited, bring to mind contemporary Beijing.

Art itself has played a key role in Barcelona's renaissance. Since the Olympics, 11 major art institutions have opened in the city. The complex in El Raval that includes Macba and Centre de Cultura Contemporània, two universities and a forthcoming library of contemporary art, was conceived as a “curatorial area” that would spur the transformation of the neighborhood.

By all accounts it is working: the area is lively, and the urban ecology that moves inexorably from artists to real estate developers to trendy professionals seems in full swing. Bookstores, boutiques featuring local designers, restaurants, small galleries and workshops, and the icily hip Casa Camper Hotel surround the museums.

But if art has changed the city, the new face of the city is also changing art. Last year Barcelona's government spent 96 million euros on the arts, confirming institutions like Macba, which opened in 1995, as major centers of cultural gravity. But institutionalization raises new questions about the role of art in the city's life.

“It is an equilibrium,” Mr. Ramoneda said. “The government pays for a play that is critical of it, but I get no political interference: there is a tradition of respect from those who fund art.”

Perhaps as a result, Barcelona lacks a robust private art market. About a dozen private galleries line a few tony blocks of Carrer Consell de Cent, just around the corner from Antonio Gaudí's Casa Batlló on Passeig de Gràcia. The handful of galleries manage a reasonable range of styles, mostly from established Spanish artists like Andrés Rábago, who as El Roto is a well-known political cartoonist. We saw his cleanly executed, nearly decorative portraits of Spanish workingmen at the Galería Jordi Barnadas. But for the most part these galleries lack life.

Until recently, the most lively arts scene in Barcelona was in the streets. But earlier this year, the city painted over most of the vibrant graffiti and stencils that had made Barcelona a requisite stop on the worldwide street art circuit, suggesting to some that institutionalized art in Barcelona is eating its young. (Cryptic black-and-white “BNE” stickers are still plastered around the city: “Kilroy Was Here” for the post-globalized artsy hipster set.)

“Artists here are the lost souls who ended up on these shores and want to express something,” said Rigo Pex, a freelance curator and musician who is also on the staff of le cool, an online events magazine based in Barcelona. With its night life, cheap food and drink and formerly cheap rent, the city has been a magnet for young people in the past decade. It became a meeting ground for artists from around Europe and the Americas — a ferment played out on the city's walls, and among ambitious arts collectives of every stripe. “Locals are easygoing,” said Mr. Pex, who is from Guatemala. “It's the visitors who have all the energy.”

But while the arts institutions have played a part in developing this scene, it is entering a new phase. As rents get higher, is development doing away with the very conditions that inspired Picasso's “Demoiselles D'Avignon”?

In a city more than 2,000 years old, how could it not be so? La Rambla was a riverbed. El Raval was a red-light district. Santa Mònica was a convent. Now it is an art space. One day it will be something else. “Es lo que hay,” said Mr. Pex, repeating a refrain of resignation: It is what it is.

Instead, up-and-coming art in Barcelona is gravitating into a shifting milieu of scrappy galleries. Almost all of them have other sources of revenue — clothes, a cafe, books. And many of the artists also do commercial work, a concession that would be familiar to Picasso, who drew menus for Els Quatre Gats at Carrer Montsió 3, where, at age 17, he had his first exposition.

Hole-in-the-wall gallery cafes like Miscelänea continue that tradition, but with Wi-Fi. If the big institutions like Macba and the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona thrive in part because of their formal connections to other institutions around the world, these leaner outfits are able to do the same via MySpace and Flickr.

When I visited, the two-person Barcelona collective BTOY was playing host to ByLOA, a show of international street art at its most lyrical and polished. More visible galleries like Iguapop and Dudua in El Borne provide outlets for both street-inflected art and more readily consumed spinoffs like books and jewelry. Iguapop, for example, is a long, white space in which gallery walls crowded with international up-and-comers like Mike Giant, Aiko and Miss Van stare down a retail side selling streetwear from Stüssy and Adidas.

Taken together, Barcelona is an ideal place to dip into many simultaneous currents of artistic expression. The juxtaposition makes it possible to see the connection between, say, Dalí and the Berlin transplant Boris Hoppek's droll “Bimbosculptures” at Iguapop, or Picasso's canvases and BTOY's stencil constructions. In Barcelona, they are brought together by an introspective rather than monumental quality.

“The purpose of art,” Mr. Borja- Villel said, “is to understand the world in which you live better. It's not about spectacle, but about understanding.”

VISITOR INFORMATION

The best openings and current shows are listed in le cool, an online guide at www.lecool.com/current.html. The company also publishes an alluring clothbound guidebook to the city, “le cool changed my life.”

At street level, the Centre d'Art Santa Mònica (La Rambla 7; 34-93-316-2810; www.centredartsantamonica.net; free admission) houses an information center on the city's arts scene. Be sure to pick up the latest ART Barcelona guide (www.artbarcelona.es).

Articket BCN includes entry to seven major exhibit spaces, including Macba, the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona, the Fundació Joan Miró and the Museu Picasso for 20 euros, or about $27 at $1.38 to the euro. Available at participating museums or (34-93) 326-2948; www.articketbcn.org.

A guide to private galleries throughout Catalonia can be found at www.galeriescatalunya.com.

SEEING ART

Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (Montalegre 5; 34-93-306-4100; www.cccb.org; entry 6 euros)

Fundació Joan Miró (Parc de Montjuïc; 34-93-329-1908; www.fjmiro.cat; entry 7.50 euros)

Fundació Suñol (Passeig de Gràcia 98; 34-93-496-1032; www.fundaciosunol.org) is a private collection of modern art newly open to the public; entry 4 euros.

Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona (Plaça des Àngels 1; 34-93-412-0810; www.macba.es; entry 7.50 euros.)

Museu Picasso (Montcada 15-23; 34-93-319-6310; www.museupicasso.bcn.es; entry 6 euros) has a collection of more than 3,000 works by the artist. The line to enter snakes down a narrow street in the Barri Gòtic.

BUYING ART

Dudua is a gallery and shop at Rossic 6 (34-93-315-0401; www.duduadudua.blogspot.com) that specializes in crafty artwork. It is the place to pick up a crocheted hot dog.

Galeria Jordi Barnadas (Consell de Cent 347; 34-93-215-63-65; www.barnadas.com) is part of the stretch of galleries along Consell de Cent.

Iguapop Gallery (Comerç 15; 34-93-310-0735; www.iguapop.net) plays host to shows by up-and-coming practitioners of international street style, and sells clothing and art books.

Miscelänea (Guardia 10; 34-93-317-9398; www.miscelanea.info) is a loungy cafe and gallery in El Raval.

MAKING ART

Artists Love Barcelona (www.artistslovebarcelona.com) is a small gallery near Macba that also runs workshops and art-intensive weeks for visitors. Five-day “painting holidays” start at 890 euros, and include accommodations and some meals.