Anavilhanas Jungle Lodge, on the Rio Negro, opened in February.

WE were in a canoe tethered to a submerged tree, fishing for piranha in the dark waters of the Rio Negro, about 125 miles northwest of the Brazilian city of Manaus. It was late afternoon, and the sun was already beginning to set behind a fleecy thicket of clouds, tingeing them with hues of purple, pink and gold. Suddenly a dolphin surfaced less than 10 feet away, carved a graceful arc in the air and then disappeared into the water again.

That night, back at the Anavilhanas Jungle Lodge, my base for that foray into the world's largest tropical rain forest, dinner — which included onion soup with sweet potato chips, an Amazonian fish called dourado prepared in ginger sauce, beef tenderloin and coconut flan — gave no hint of our rugged surroundings. Nor did the air-conditioned cottage where I slept, with its elegant tropical wood paneling and modern tiled bathroom. The next morning, I sought refuge from the overpowering heat and humidity in the lodge's swimming pool, where I watched boats of all shapes and sizes putt-putting their way up and down the river.

Not too long ago, options for visitors to the Brazilian Amazon region were limited: you flew to Manaus, stayed at the Tropical Manaus Hotel on the outskirts of the city, and took day trips to the edge of the forest. But that, thankfully, is no longer the case. Responding to the international boom in ecological and adventure tourism, lodgings have sprung up all over the region in the past four or five years. Travelers with a yen for the exotic and a tolerance for the unpredictable can now book a stay in the jungle with an expectation of, if not luxury, then at least a reasonable degree of comfort. ( Still, don't be surprised when you see signs like these, posted in the rooms at the Tiwa Amazonas Ecoresort, just across the river from Manaus: “Warning: The simultaneous use of the shower and the air conditioner is forbidden!”)

There are easily a dozen of these new hotels — a type of lodging I couldn't have imagined when I started traveling in the Amazon 30 years ago, often sleeping in grimy hammocks in $3-a-night fleabags with dirt floors. The main concentration is on the Rio Negro, to the north and west of Manaus, where the tannic acid that darkens the water and gives the river its name inhibits mosquitoes from breeding, so visitors don't have to worry as much about malaria or dengue or other typical tropical maladies.

And there are more lodgings to come. The most ambitious is a 102-room complex being built just off the road to the town of Novo Airão by the Accor group of France, which is scheduled to open in 2010 and will be the first international luxury chain hotel actually in the jungle; the Hilton company has also announced plans to build a 196-room “eco-lodge resort” near Novo Airão .

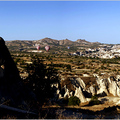

For the moment, however, the Anavilhanas Jungle Lodge, which opened in February, is the newest and perhaps the most chic example of the lodge phenomenon. Operated by a couple from São Paulo, it is on a bluff above the Rio Negro, within sight of the Anavilhanas Ecological Station, a government nature reserve that encompasses the world's largest riverine archipelago, with more than 400 islands and hundreds of lakes and igapós, an indigenous word that means flood forest. Astonishingly rich in both animal and plant life, the reserve area, which has been designated a Unesco World Heritage site, is unspoiled and uninhabited.

No matter what their location, the lodges tend to follow a certain pattern when it comes to outings. In the morning, for instance, before the heat gets too stifling, a nature walk is, more often than not, de rigueur; I've seen all sorts of monkeys, macaws and toucans, not to mention sloths and anteaters, on such treks. Afternoon excursions to fish for piranha provide the kind of bragging rights that delighted my teenage son when I took him with me on an Amazon trip a few years ago.

After dinner, it's often back to the boat to hunt for the Amazonian caiman known as the jacaré. But instead of carrying guns or spears, guides are armed with powerful spotlights that freeze the reptiles in position and make it possible to remove young ones from the water so that guests can run their hands over their cool, ridged carapaces.

All can arrange an excursion for you to witness the “meeting of the waters,” the spot just southeast of Manaus where the Rio Negro's dark waters converge with those of the Amazon's other major tributary, the Solimões. I've stopped there at least a dozen times and never cease to be amazed at the way the two great rivers, markedly different in color and temperature, collide with such force and volume that they seem to be fighting each other.

But each lodge also tries to offer something its competitors do not. For instance, the Amazon Ecopark Jungle Lodge, 40 minutes from Manaus, is famous for its “Monkey Jungle Reserve.” Here, woolly monkeys, some confiscated from contraband dealers, others injured, are monitored at a rehabilitation center on the lodge grounds.

At the Anavilhanas Jungle Lodge, a group of more than a dozen botos, or gray dolphins, show up daily to be fed at nearby Novo Airão. A motorboat from the lodge takes guests to a floating restaurant alongside the main dock there, where a pet anaconda circulates among customers sipping chilled beers or soft drinks. As we stood on a raft attached to the restaurant, the dolphins cavorted, sticking their long snouts up from the water for pieces of fish tossed their way or seizing fish snacks from tourists intrepid enough to go into the water.

“If we'd let the botos, they would spend the entire day here, just eating,” said Marisa Grangeiro de Almeida, whose family operates the restaurant. “But the environmental agency and the university scientists have established fixed feeding hours.”

The Anavilhanas Jungle Lodge has its own strict rules when it comes to the guides it employs. Most lodges rely on freelancers who come in from Manaus. The Anavilhanas lodge hires only residents, which quickly pays off for the visitor. My guide, Célio Silva Nascimento, not only knew all the best fishing spots and how to navigate tricky river channels that come and go with the seasons, but also had detailed knowledge of local flora and fauna, no matter how obscure.

That is important because the sheer abundance of wildlife on view can be staggering, especially as one gets farther away from Manaus. I have never seen as many birds, for example, as I did two years ago at the Pousada Uacari, which is situated inside the Mamirauá nature reserve, 350 miles west of Manaus at the confluence of the Solimões and Japurá Rivers. Startled by the sound of our motorboat, huge flocks of snowy egrets, herons, cormorants, kites, tinamous, bitterns, ospreys and curassows took to the air as we navigated an igarapé, or narrow tributary.

Like several of the new lodges in the region, the Pousada Uacari is not on land, but sits on floating rafts at a bend in the river. Here guests can view wildlife in remarkable proximity. After dark, for instance, I could see caimans, some as large as eight feet, their eyes glowing like orange lanterns; some came startlingly close, banging against the dock and making querulous grunts, a symphony that continued through the night.

There is even a lodge that is literally up in the trees. The Ariaú Amazon Towers, opened in 1987 and recently expanded and modernized, is a two-hour boat ride northwest of Manaus. One of the oldest and by far the largest of the jungle lodges, it has been visited by celebrities like Bill Gates and the King and Queen of Spain. All 269 rooms are up in the jungle canopy, as much as 60 feet above the river, and connected to one another and the dining hall and common areas via aerial walkways.

Only one lodge that I know of can claim to be on the Amazon River itself. The Amazon Riverside Hotel makes the most of that distinction, offering excursions to see the sun rise from a century-old British-built navigation beacon in the middle of the river; it also has a nature trail that leads to a hilltop observation post with a commanding view of both the jungle and the river, and has arranged hammocks at the dock for guests keen on doing nothing but watching the river flow.

Just to remind guests where they are, the Amazon Riverside's reception area, built around a lagoon, displays the outsize skulls of an adult caiman and a toothy onça, the Brazilian cougar. Lined up near the dining area is a series of jars with pickled remains of some of the animals that have been found on or near the hotel grounds: poisonous snakes, scorpions and spiders, including a giant caranguejeira, or crab spider.

The owners of the Amazon Riverside are members of Manaus's flourishing Japanese community, which migrated to the region nearly a century ago to work on jute and pepper plantations. The Tsuji family caters to Japanese tourists, an effort that is reflected in an innovative menu that includes dishes such as sashimi of tambaqui, a prized Amazon game fish, and tempura made with okra and abóbora, the Brazilian equivalent of pumpkin.

The piranha fishing there was extraordinary. On a Sunday afternoon I ventured out in a small motorboat with a couple from the Tokyo area, Satoshi Tatsumi and Kazuko Ito, and in less than two hours, we caught nearly two dozen piranha, the largest of which we took back to the hotel and ate in a tasty stew. The piranha were so plentiful that Satoshi, a martial arts instructor who was wearing a cast on his arm because of an injury suffered in a competition, was able to catch them one-handed with nothing more than a simple bamboo pole and small pieces of beef as bait.

Many lodges organize visits to the homes of people who live nearby, at the river's edge in houses usually on stilts. Known in Portuguese either as caboclos, a term equivalent to hillbilly, or more respectfully as ribeirinhos, or river dwellers, they have limited incomes and little contact with the rest of Brazil. If you've never seen liquid latex being roasted on a spit over a fire to be made into rubber or if you don't know how manioc is turned into the golden flour that is one of the Amazonian staples, then take one of these tours.

But sometimes there is an element of exploitation that I find unsettling. The Amazon Riverside Hotel pays the river-dwelling families that its guests are taken to see, but some other lodges do not. When I was visiting another lodge, I was taken to the home of Iraci Cantuária dos Santos, the 67-year-old matriarch of a family of eight. I asked her whether she would make any money from our visit. She replied, “Only if you buy something,” and pointed to herbs and carved wooden animals for sale.

To the river dwellers all visitors seem impossibly well-off. But luxury, of course, is a relative concept. The reality is that it is tremendously difficult and expensive to bring in fuel, food and other supplies by boat, and no Amazon lodge I've visited would ever qualify as a five-star resort.

You are, after all, in the heart of the Amazon jungle, and your accommodations, no matter what they might lack in grandeur, would have been the envy of the area's first European explorers. They came looking for “El Dorado” and found a “green hell” instead. Fortunately, you, the 21st-century traveler, now have other options.

VISITOR INFORMATION

HOW TO GET THERE

Until mid-2006, getting to Manaus from the United States was a cumbersome process that often involved flying to Rio or São Paulo and then doubling back. But Brazil's TAM Airlines (www.tam.com.br) now operates a daily five-hour flight from Miami. A round trip in late September or October starts at $1,025; Copa Airlines (www.copaair.com) also has flights from $969, but those include a stop in Panama.

WHERE TO STAY

The packages mentioned are per person and include three meals a day. Except as noted, transportation from and back to Manaus is also covered.

The Anavilhanas Jungle Lodge (55-92-3622-8996; www.anavilhanaslodge.com) has been open for only about six months, and is perhaps the most elegant lodging in the Amazon. It has 16 air-conditioned, wood-paneled rooms decorated with regional art, and an open-air common area stocked with DVDs and books. The minimum two-night package is 950 reals total, or $475 at 2 reals to the dollar.

Unlike most other new lodges, the Amazon Riverside Hotel (55-92-3622-2789; www.amazonriversidehotel.com), which opened in 2002, is 40 minutes downstream from Manaus, not upstream. As a result, transportation to the hotel includes a visit to the site where the Rio Negro and the Solimões join to form the Amazon. There are 15 rustic apartments, with fans but no air-conditioning. The one-night package is 625 reals; the hotel also offers a day-use option for 250 reals.

The main lure of the Pousada Uacari (97-3343-4160; www.uakarilodge.com.br) is its privileged location, in the Mamirauá nature reserve about 90 minutes by speedboat from Tefé, which is on the banks of the Solimões River. There are 5 floating wood cabins, offering a total of 10 rustic apartments, with water for the showers and sinks coming directly from the river. The minimum three-night package of 1,000 reals a person does not include transportation from Manaus to Tefé.

In a competition for most unusual setting, the Ariaú Amazon Towers (55-92-2121-5000; www.ariau.tur.br) would win hands down. Just off the west bank of the Rio Negro, its 269 rooms, some with air-conditioning, and trees growing through them, are up at the level where monkeys live. One night costs 860 reals.

The Tiwa Amazonas Ecoresort (55-92-9995-7892; www.tiwa.com.br), which opened in 2003, has 52 air-conditioned rooms on stilts over a lagoon, plus a common area with a restaurant, bar, game room and a view of the Manaus skyline. One night is 595 reals.

Less than an hour from Manaus by boat, the Amazon Ecopark Jungle Lodge (55-21-2256-8083; www.amazonecopark.com.br) has 64 rooms and 3 bungalows, a beach on the Rio Negro and a pool. At 11 a.m. and 5 p.m., there are opportunities to feed the monkeys. One night is 720 reals.

WHEN TO GO

“In September, October and November, the water levels are quite low,” said Wedson Franklin Santos, a guide who works at the Amazon Riverside Hotel, “so you get to see all the exuberance of the wildlife,” which is forced out into the open. He added that during the middle of the year, when the flood plain is starting to recede, “the attraction is more the landscape itself and not the animals, which are mostly in hiding.”

STAYING HEALTHY

Most doctors recommend a program of antimalarial medicine, beginning several weeks before arrival and continuing during a trip. (I stopped taking such prophylactics because of the unpleasant side effects, and besides, there is now a drug-resistant strain of malaria.) But there are other measures one can adopt to reduce the risk of mosquito-borne diseases like malaria and dengue. Rather than going outdoors with arms exposed, for example, wear a long-sleeve shirt made from a lightweight fabric. And do your best to avoid being outside during the period local people call “the malaria hour,” about 5 to 7 p.m.

LARRY ROHTER, who has just completed eight and a half years as chief of the Rio de Janeiro bureau of The Times, is on leave, writing a book about Brazil.