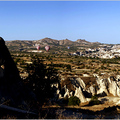

Wake turbulence was captured in this photo of a British Airways flight descending through thin clouds near London last July.

People who fly a lot tend to be nonchalant about the experience — until the plane hits a patch of choppy air. Then, as cups start skidding across tray tables and luggage jostles overhead, even some frequent fliers admit to gripping the armrest with fear.

“Logically and rationally, I know that planes are designed to withstand pretty severe amounts of turbulence before anything bad would happen,” said Lawrence Mosselson, who works for a commercial real estate company in Toronto and flies about 50 times a year. “And yet I find that at the first sign of any turbulence, I’m almost paralyzed in my seat.”

Industry experts say turbulence rarely causes substantial damage to an aircraft, especially as systems to detect and respond to it have improved. Most of the injuries caused by turbulence, they say, could have been prevented by a decidedly low-tech measure: a seat belt.

“The airplane is designed to take a lot more aggressive maneuvering than we are,” said Nora Marshall, chief of aviation survival factors at the National Transportation Safety Board. “We see people getting injured in turbulent events because they’re not restrained.”

Because of the way the safety board defines an accident — an event involving substantial damage to the aircraft, a death or a serious injury — the agency has officially investigated 94 accidents in the past decade involving turbulence as a cause or factor. Almost all were classified as accidents because 119 people (mostly flight attendants) suffered serious injuries, ranging from broken bones to a ruptured spleen. Only one of the accidents involved substantial damage to the aircraft.

The safety board attributed one death to turbulence over that time. In 1997, a Japanese passenger on a United Airlines flight from Tokyo to Honolulu was jolted out of her seat when the plane encountered turbulence; she suffered fatal injuries when she hit the armrest on the way back down. According to Ms. Marshall, who participated in the investigation, the woman was not wearing her seat belt, perhaps because the announcement advising passengers to keep seat belts fastened while the seat belt sign was off was not translated into Japanese.

That announcement is required by the Federal Aviation Administration. But Ms. Marshall said most passenger injuries still involved people seated without being buckled in. Including minor injuries, like a cut or a twisted ankle, safety board data indicates that about 50 people a year suffer turbulence-related injuries. But that is only the number of accidents the agency investigates, so the true figure is higher.

Now for the reassuring part: the plane should be able to handle the turbulence.

“People really shouldn’t be too concerned about the airplane having difficulty in turbulence — it’s designed for turbulence,” said Jeff Bland, senior manager for commercial airplane loads and dynamics at Boeing, adding that structural failures because of turbulence are rare.

Although there have been airplane crashes where turbulence was a factor, accidents typically involve multiple factors so it is often impossible to say that turbulence caused a crash. Industry and safety officials agree that such accidents have become unlikely as more has been learned about turbulence.

According to Mr. Bland, aircraft manufacturers have been collecting data since the 1970s to determine the maximum stress that planes experience in turbulence, and they then design aircraft to withstand one and a half times that. In fact, a video clip available on YouTube shows Boeing’s test of the wing of a 777; using cables, the wing is bent upward about 24 feet at the tip before it breaks.

Systems to detect and respond to turbulence have also improved, including the technology that automatically adjusts to lateral gusts of wind. And Boeing’s 787 aircraft will have a new vertical gust suppression system to minimize the stomach-churning sensation of the plane suddenly dropping midair.

Pilots say those drops are typically no more than 50 feet — not the hundreds of feet many passengers perceive. They also emphasize that avoiding turbulence is mostly a matter of comfort, not safety.

“The mistake that everybody makes is thinking of turbulence as something that’s necessarily abnormal or dangerous,” said Patrick Smith, a commercial pilot who also writes a column called “Ask the Pilot” for Salon.com. “For lack of a better term, turbulence is normal.”

A variety of factors can cause turbulence, which is essentially a disturbance in the movement of air. Thunderstorms, the jet stream and mountains are some of the more common natural culprits, while what is known as wake turbulence is created by another plane. “Clear air turbulence” is the kind that comes up unexpectedly; it is difficult to detect because there is no moisture or particles to reveal the movement of air.

Pilots rely on radar, weather data and reports from other aircraft to spot turbulence along their route, then can avoid it or at least minimize its effect by slowing down, changing altitude or shifting course. But even with advances in technology, it is not always possible to predict rough air.

“We still don’t have a really good means in the cockpit of seeing turbulence up ahead,” said Terry McVenes, a pilot who serves as executive air safety chairman for the Air Line Pilots Association. “Sometimes we can prepare ourselves; other times it does sneak up on us.”

Yet that has not deterred some fearful fliers from trying to gauge whether they are going to have a bumpy ride. Peter Murray, a computer network administrator from Lansing, Mich., created TurbulenceForecast.com to offer nervous fliers like himself a way to view potential turbulence along their flight path.

At the time, he was frequently flying to Baltimore to visit his girlfriend, and would sometimes change his flight if it looked as if he would encounter choppy air. “I have never been in anything that could even be considered light turbulence because I could avoid it so well,” he said.

But for those unable to avoid a shaky situation, technology also offers more ways to cope. That is why Tim Johnson, a frequent flier who works for a satellite phone company in Washington, posted a question on the forums at Flyertalk.com asking other travelers about their favorite turbulence tunes. (His choice was the “Theme From ‘Rawhide’ ” on “The Blues Brothers” soundtrack. Other suggestions included “I Will Survive” by Gloria Gaynor and “Free Fallin’ ” by Tom Petty.)

“I was on an A340 and it was flying all over the place,” Mr. Johnson said, recalling a particularly bumpy flight. “But something about that song had me laughing out loud.”

At least these days, he added, “You’ve got a lot more tools to distract you.”

That is, as long as your iPod does not fly out of your hand.